Che Buford accomplished something most violinists will claim is nearly impossible: using Youtube videos, he taught himself to play the violin entirely by ear. He was 11 years old. He first heard the sound of a violin one year earlier, during a recital at his elementary school in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. “I was so intrigued by the sound the instrument could make, it inspired me to learn to play,” he said. Two years later he would take his first lesson, and five years after that he would step foot on the most famous stage in New York, Carnegie Hall.

At 19, Che is currently in his second year at conservatory. Quiet and gentle, his subtle confidence belies a rise to success in the ruthlessly competitive world of classical music, where the now-ubiquitous conversation about diversity, equity, and inclusion has only just begun to meaningfully impact a Eurocentric musical culture.

Despite the enormous influence of musicians of color on nearly every genre of music, the classical music field remains starkly white and Asian. In 1996, Black and Latinx musicians comprised one percent of American orchestras. Today, their ranks have increased to just four percent, according to data compiled by the League of American Orchestras. Leadership of the world’s prominent musical institutions remains similarly homogeneous, with people of color representing only one percent of orchestra executive directors. The New York Philharmonic, the oldest symphony orchestra in the United States (founded in 1842), did not have a single African American principal player in its ranks until 2014, when Anthony McGill was hired as principal clarinetist.

Read More on Medium…

By Sam Anderson

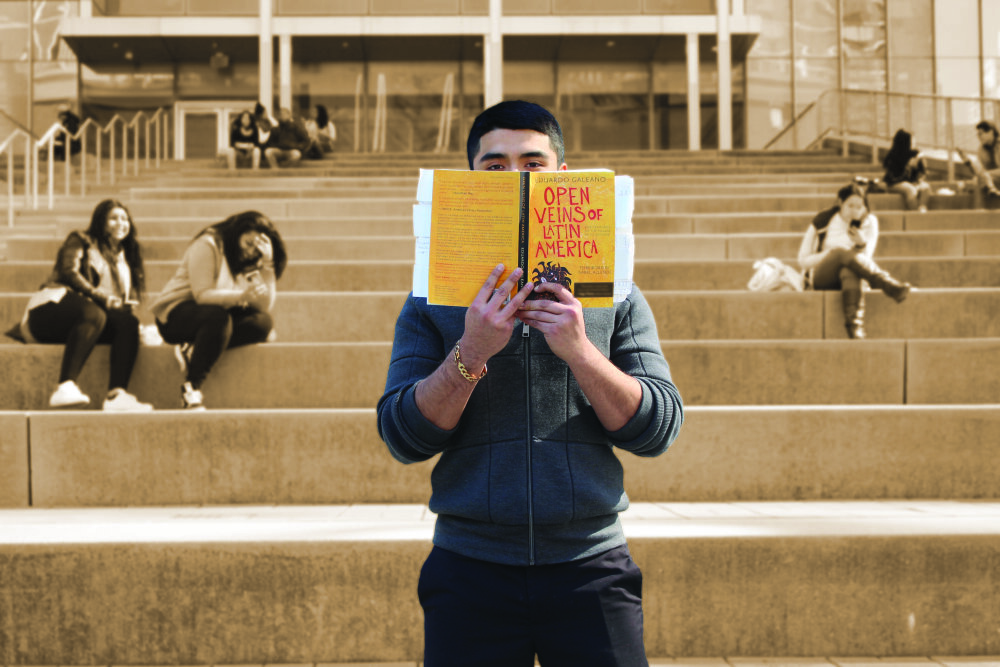

Of the roughly 11 million undocumented immigrants living in the United States, nearly 10 percent live in New York State. Many of these immigrants live, work, and go to school in New York City. At John Jay College, 220 students self-report that they are undocumented, and another 280 have missing or unclear citizenship status, according to CUNYfirst, the database of student management. Calculating the exact number of undocumented students at John Jay is intrinsically difficult, and, according to Professor Isabel Martinez, the difficulty is compounded by the fact that most undocumented immigrants underreport, and that many live in mixed-status families. Still, a realistic estimate of the number of undocumented students at John Jay puts it between 500 and 1,000, or roughly 3 to 6 percent of the student body.

Some of these aspiring lawyers, criminologists, forensic scientists, cybersecurity specialists, police officers, and fierce advocates for justice refer to themselves as “Dreamers.” Many came to the United States as children or infants. Some have never seen their country of origin. To the Dreamers, the U.S. is the place they call home.

Some of these students have their legal status protected under DACA, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy put in place under President Obama. Yet even for them, college life is fraught with difficulty. Most are ineligible for state or federal financial aid. They often work full-time jobs to pay for tuition, and it is not uncommon for students to drop out for a semester, save money, and return. Still, they persevere, motivated by the thought of achieving their degrees and moving ahead to jobs, graduate schools, or other opportunities. For them as well as for their families, this is the American dream.

In general, students and families without criminal records have not been among those targeted for deportation by the federal government. That changed when President Trump announced an executive order that significantly broadened the power of Customs and Border Protection to deport undocumented immigrants. For the most vulnerable student population at John Jay, things just got a lot more uncertain.

“We all know someone who’s undocumented, whether we know it or not,” said Sofia (not her real name), a junior Sociology major at John Jay. “DACA gives me a privilege, and I need to remember that even though I’m less likely to be deported, it does not mean that the fight for the undocumented community is over.” Sofia’s sister is also DACA-protected, which means that for now, they are not at risk of deportation. But the same can’t be said for their parents, who moved here in 2004 when their home country of Peru underwent a sharp economic downturn. Now, Sofia worries about her father leaving the house to get groceries.

Such fear is common among undocumented students. The challenge of paying college tuition, previously their greatest source of anxiety, pales in comparison to the thought of losing a family member to deportation.“

As a professor, my main goal is to teach my students,” said Martinez, an assistant professor of sociology. “That means helping them develop research skills, writing skills, reading skills, and a body of knowledge. I can’t do that if my students are terrified and can’t concentrate.”

Martinez also serves as Director of U-LAMP, the Unaccompanied Latin American Minor Project, which provides support to young immigrants in removal proceedings. She is one of the John Jay faculty members who sprang into action after Election Day, reaching out to students she knew were undocumented to offer support. Martinez has been coordinating with John Jay’s DREAMers Club to organize “Know Your Rights” workshops, where students learn practical skills that can help them and their families avoid deportation.

Some of the tips that have been shared with students include teaching them how to spot the difference between a judge’s warrant and a warrant from the Department of Homeland Security, which doesn’t hold up in court. “They have the right to not open the door if ICE agents come to their homes without a warrant from a judge,” Martinez said, referring to Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Martinez has also been distributing cards that contain the person’s name and the words “

I invoke my right to remain silent.” She explained: “Trouble happens when conversations with Customs officers give people the opportunity to say something that might have bad consequences. With this notecard, you can invoke your rights without saying anything.” Immigrants without documentation are also gearing up for an increase in expedited removals. To protect themselves, Martinez recommends that all immigrants carry proof that they’ve been in the country for more than two years. Sofia says she always knew she was undocumented, but adds: “It didn’t impact me until I graduated from high school. Filling out college applications, I realized that I was not eligible for financial aid, and that I needed to work in order to continue my education.”

She’s no stranger to work, having had off-the-books jobs since she was 15. One experience stuck with her: “My first job was cleaning a high school on Long Island. The supervisor saw how tired I was after working from eight in the morning to seven at night. He said to me, ‘Why are you tired? This is going to be your future.’ I still remember that today, because this is how society looks at undocumented people and Latinos in general.”

That supervisor might be surprised to learn that Sofia will soon complete her bachelor’s degree and plans to go to law school.

“There’s an assumption in America that everyone here has an equal opportunity,” said Robbi (not her real name), an undocumented John Jay student from Pakistan. “Everyone assumes you’re on the same page, that you qualify for the same things, but it’s not true. We have to go through so many different hoops to finance our education.”

The freshman Economics major said she feels an additional level of anxiety as a Muslim. She was 3 or 4 when her family emigrated from Pakistan, and now she feels unable to leave. “I would like to see where I was born and visit my family, but now I don’t plan to leave whatsoever,” she said.

Sofia, too, experienced being unable to leave the United States when she had to turn down a study-abroad trip to Mexico. She had been accepted into a program to study indigenous Mayan communities, but because the group was set to return on Jan. 22, two days after Trump took office, she was advised to decline the opportunity. Sofia said that she will likely avoid all plane travel in the foreseeable future to avoid being detained at the airport.

Far from being isolated cases, these incidents are representative of the experiences of other undocumented students in the CUNY system and at colleges and universities nationwide. Many undocumented students who were brought to the U.S. as children and have lived their entire lives as Americans are now realizing the limitations of their status in applying for jobs, financial aid, and other programs. And, since the presidential election, they have the added worry of being separated from their families, and the possibility of being sent back to a country they do not remember.

At John Jay, organizations like the DREAMers Club provide a safe space to talk about these issues and raise questions about what to do next. Olivia Ramirez, the president of the DREAMers Club, is a child of immigrants, a native-born citizen, and recently she has become acutely aware of just how much privilege her legal status confers.

“I’ve worked with students who aren’t DREAMers and who don’t have DACA, they are just undocumented students without support,” she said. “Having no financial aid and working 40-plus hours per week seriously affects their academics. There’s not enough time to do homework, and many of them are also supporting their families. They have to decide, do they eat and sleep, or work on homework. These are hard decisions to make.”

Ramirez says she was reluctant to run for president of the DREAMers Club because she hadn’t experienced firsthand what it is to be undocumented. But she decided to run in order to leverage her connections with other organizations on and off campus, like Legal Aid, Single Stop, CUNY Citizenship Now!, Make the Road, and U-LAMP. In addition to coordinating events, panels, and workshops, a big part of the DREAMers Club is simply providing a space to talk, connect, and share a common experience.

“The Dreamers are in a sense trying to become more empowered to tell people they’re here and unapologetically undocumented,” Ramirez said. “There are some who want to stay in the shadows, and others who want to raise their voices and say ‘we’re here and we’re going to fight to stay here.’”

The diversity of opinion on whether or not undocumented students should be outspoken about their status is reflective of the political climate—people simply do not know how severe the risk of deportation will become, or what the future holds for DACA. “We’re in a whole new ball game,” Martinez said.

By Samuel Anderson, Special to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle

Salman Rushdie (right), this year’s recipient of the Mailer Prize for lifetime achievement, speaks to writer Randy Boyagoda at a ceremony at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn on Thursday. Eagle photo by Sam Anderson

Before Rushdie and Anderson took to the stage Thursday night as honorees at Pratt Institute, including Rushdie receiving the Norman Mailer Center Lifetime Achievement Prize, they gave the Eagle a few words on topics close to their bodies of work.

Rushdie, whose fiction often explores post-colonial issues and the threat of radical ideology, spoke about his defense of free speech and gave his opinion on the heightened fear of terrorist attacks. Throughout the evening, he remained completely at ease, despite the camera flashes bursting around him. He has a wry smile and a voice laced with subtle detachment, enhanced by his British-Indian accent.

Sam A. – On your Wikipedia page it says you have won 31 awards.

Rushdie – Really? Does it say that? I have no idea.

Sam A.– Tonight makes it 32. What is the importance of a literary award today?

Rushdie – Well, lifetime achievement is lifetime achievement. It’s nice to know that people recognize a long body of work. This year makes it 40 years since I published my first book, so if somebody wants to say “well done,” I’m for it. And I really admire the work of the Norman Mailer Foundation. It’s nice to be able to contribute to what they’re doing.

Sam A. – Your work has been called politically polarizing. Do you have a political agenda, or does that come by happenstance?

Rushdie – I really don’t. In fact, less and less these days. I think that some of my earlier books were more directly political, like “Shame.” But nowadays, I don’t think my books are political anymore. There was just one book that was.

Sam A.– After the Charlie Hebdo attacks last year, you were very outspoken in your defense of free speech and your support of those journalists. Given the attacks in Paris recently, have you continued your position?

Rushdie – Yes, and I think it’s even more important now. And it wasn’t just me. But there were a lot of writers who were disappointed with the protests. [Some members of the prestigious literary group protested PEN granting its Freedom of Expression award to Charlie Hedbo, which they viewed as a culturally intolerant publication]. People like Ian McEwan and Don DeLillo, who’s here tonight, Paul Auster and Adam Gopnik. A lot of writers were as disappointed as I was, and wrote and spoke about it. On the whole, that protest was a very small part of the PEN membership. It was disappointing, you know?

Sam A. – As a supporter of free speech, would you support Donald Trump’s right to propose a ban on Muslims?

Rushdie – No, don’t be silly. I defend his right to say it, but I also defend my own right to call him a jerk [chuckles].

Sam A. – And you’ve dealt a lot with Muslim extremism in your works. Currently, we are dealing with what people are calling “home-grown radicalization” here in this country. Do you have any comments on that, given your understanding of these issues?

Rushdie – Well I think it exists, though it’s small. To my mind, the real radicals in this country are white Christians. Just look at all the terrorist attacks that people are afraid of. Terrorist attack on a school — already happened; terrorist attack on a campus — already happened; terrorist attack on government buildings — already happened. None of them were perpetrated by Muslims. They were done by crazy white people with guns. It seems to me that if you were to look for a terrorist organization in this country, you should look at the NRA. Let’s look at the right problem.

Sam A. –Last year, you mentioned, in reaction to the Charlie Hebdo attacks, that a divide had occurred between ordinary Muslims and extremists. Do you think that is the case today?

Rushdie – I think ordinary Muslims are as terrified of ISIS as anyone else. And in many ways, more disappointed, because it tars them with that brush.

* * *

Laurie Anderson, pre-eminent musician and avant-garde performing artist, spoke on the importance of art and the role of experimentation in its creation. During the interview, Anderson was quick to show excitement, and her eyes shone with a bright, winking humor. She was the only woman among the guests of honor when they posed for press photos.

Sam A. – You’ve been at the forefront of experimental art for quite some time now. Can you tell me why experimental art is important?

Anderson – It’s not more important than any other art. Why is art important? Because it’s about freedom. Although experimental art does tend to cut more of the bonds than other forms. You use less of the rules, break more of them, be more free in form.

Sam A. – Can you tell me about this new installation/performance piece you’ve been working on, which involves a detainee from Guantanamo Bay, and confronts issues of identity and security among other things? [Anderson describes her new piece in The New Yorker].

Anderson – Making this piece, I learned to never underestimate the audience. Mohammed el Gharani was captured when he was 14. He was a prisoner until 21. He was tortured, but never charged, and finally, just kind of dumped. So, I’m interested in stories, and his story versus the U.S. government’s story is just fascinating to me.

Sam A. – Do you consider yourself to be a political artist?

Anderson – Not particularly. I think all art can be considered in that light, if you want to look at it that way. I don’t think there’s anything more engaged about being specifically political. I could look at a giant blue painting and it would give me more of a sense freedom than some long, polemical work of art that’s about, like, being free. You know what I’m saying? Art works on your eyes, and your ears, and it just makes you feel a certain way. I don’t have anything against polemical art either. I like all art. Except [smiles] musical comedy. You’d have to kill me to get me to go to one.

Sam A. – Do you ever worry that because of how experimental or avant-garde your work is, it might not have access to as wide of an audience as more mainstream artists?

Anderson – I’m a snob! [ Laughs] I don’t care about getting my message to the millions. I’m enough of a snob to say that the more people that like it, maybe the less daring it actually is. I’m from the art world, and accidentally, once in a while, I might drift into the pop world or some other world, but that’s not my goal at all.

Sam A. – Who are you looking at right now, who are your favorite artists of 2015?

Anderson – You know what, my favorite artist is usually the one I just saw. So I’d have to say, Christian McBride [virtuosic jazz bassist], because I saw his show last night at the Vanguard.

Sam A. – How was it?

Anderson – Beyond awesome! It was so great, I mean this guy is a killer player. And he had a band, it was the second night he worked with the band, and it was deeply musical and deeply inventive. I was just jumping up and down every other phrase going “yes!”

Sam A. –You’ve been in New York for a very long time, tell me what you still love about this city and what you hate about it.

Anderson – What do I love? Russ and Daughters whitefish chowder. It’s the best restaurant in New York. What do I hate? It’s a little too crowded. But you could say that about the world.

December 16, 2015 - 12:55pm